Residents

Many Lives Intertwined

Over the thousands of years of human habitation on the grounds of the Trent House, people from many origins and cultures have lived on the site. The Trent House Association is engaged in a long-term effort to research and present information on this rich history. Currently, the focus is on deepening our understanding and interpretation of the lives of people of African descent who lived and worked at the Trent House site, many enslaved during the colonial period. As part of this effort, the Trent House Association co-founded the Sankofa Collaborative with its partners, 1804 Consultants, the Stoutsburg Sourland African American Museum, and the Grounds For Sculpture. Following the Collaborative’s first invitational symposium in January 2017, it has held numerous workshops for wide-ranging audiences with the goal of helping to help individuals in schools, museums, libraries, cultural institutions, and civic groups present, interpret, and discuss African American history.

Archaeological research on the Trent House grounds has uncovered artifacts from Native American life, both before and after European colonization. The Association is beginning to explore how to engage New Jersey’s American Indian communities in incorporating this rich heritage into the Museum’s exhibits and presentations. Please see the "Archaeological Investigations" tab under "Discover" for more information on archaeological findings relating to the indigenous people of this land.

From Trent’s death in 1724 to 1929 when the House and remaining property were given to the City, there were many residents – the wealthy men who owed or rented it, their families, and enslaved, indentured, or paid servants. Using documents such as wills and census records, we have been able to add names to many of these individuals, though some remain unknown. Click here for a listing of the inhabitants of the House from the Trents to the Stokes. As we learn more, we will continue to expand the stories we can tell about the many people who have lived on the land we now know as Trenton, New Jersey.

Archaeological research on the Trent House grounds has uncovered artifacts from Native American life, both before and after European colonization. The Association is beginning to explore how to engage New Jersey’s American Indian communities in incorporating this rich heritage into the Museum’s exhibits and presentations. Please see the "Archaeological Investigations" tab under "Discover" for more information on archaeological findings relating to the indigenous people of this land.

From Trent’s death in 1724 to 1929 when the House and remaining property were given to the City, there were many residents – the wealthy men who owed or rented it, their families, and enslaved, indentured, or paid servants. Using documents such as wills and census records, we have been able to add names to many of these individuals, though some remain unknown. Click here for a listing of the inhabitants of the House from the Trents to the Stokes. As we learn more, we will continue to expand the stories we can tell about the many people who have lived on the land we now know as Trenton, New Jersey.

Before Trent

The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation

The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation

First Residents

Humans first reached the east coast around 12,000 years ago. Their descendants who lived in what became New Jersey were the Lenni-Lenape. Lenni-Lenape translates to "we, the people".

The land on which the Trent House was built is part of the traditional territory of the Lenni Lenape, called “Lenapehoking.”

Indigenous Life Before European Contact

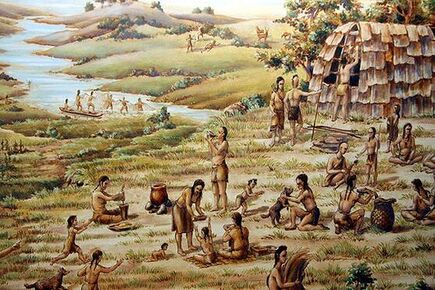

Indigenous people in New Jersey began to garden about 900 CE (Common Era). They grew corn, beans, squash, and harvested wild berries and fruits. The Lenape had knowledge of healing plants and used them to treat ailments. They hunted and fished, as well.

The Lenape society was matrilineal. Lineage was traced through the mother's side and clan affiliation was determined by the mother. When they got married, Lenape were expected to marry outside of their clan, and husbands lived with their wives' families. Lenape lived in small villages organized by clan, and lived in wooden longhouses.

Women held important community positions and were in charge of most of the land. However, labor was divided by sex, but was equal. In general, men hunted and protected their villages, and women gardened and took care of household tasks. Children learned how to do tasks by watching elders of their own gender.

Humans first reached the east coast around 12,000 years ago. Their descendants who lived in what became New Jersey were the Lenni-Lenape. Lenni-Lenape translates to "we, the people".

The land on which the Trent House was built is part of the traditional territory of the Lenni Lenape, called “Lenapehoking.”

Indigenous Life Before European Contact

Indigenous people in New Jersey began to garden about 900 CE (Common Era). They grew corn, beans, squash, and harvested wild berries and fruits. The Lenape had knowledge of healing plants and used them to treat ailments. They hunted and fished, as well.

The Lenape society was matrilineal. Lineage was traced through the mother's side and clan affiliation was determined by the mother. When they got married, Lenape were expected to marry outside of their clan, and husbands lived with their wives' families. Lenape lived in small villages organized by clan, and lived in wooden longhouses.

Women held important community positions and were in charge of most of the land. However, labor was divided by sex, but was equal. In general, men hunted and protected their villages, and women gardened and took care of household tasks. Children learned how to do tasks by watching elders of their own gender.

|

Based on European accounts, the Lenape were tall and healthy. They often adorned themselves with body paint and tattoos. They wore clothes made out of skin and fur; the least amount of clothing in the summer months, and many layers in the winter.

The spiritual beliefs of ancient the Lenape cannot be completely verified. They believed that the world was made by a Creator. Like other indigenous American groups, they believe that the land now known as North America is called Turtle Island. The Lenape considered everything around them to have a spirit--good or bad. |

Native American Life During the Early Colonization Period

European traders encountered Native Americans in New Jersey around the year 1600. Later Europeans came with the goal of creating permanent settlements. Archaeological evidence and written history show that the two groups of people exchanged goods. Native Americans traded things like pelts for European objects such as glass beads, metal tools, and alcohol.

European traders encountered Native Americans in New Jersey around the year 1600. Later Europeans came with the goal of creating permanent settlements. Archaeological evidence and written history show that the two groups of people exchanged goods. Native Americans traded things like pelts for European objects such as glass beads, metal tools, and alcohol.

|

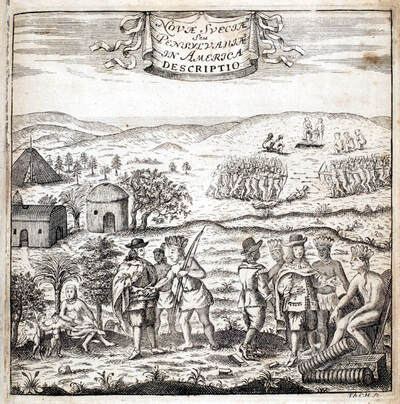

The first colonists were the Dutch, followed by Swedes and Finns, then the Germans and English. Sometimes, the colonists purchased land from Native Americans, though they paid small amounts of Europeans money or objects. These "purchases" disregarded the fact that the Lenape believed all land belonged to all people and living things. The Lenape believed these purchases were agreements to share the land with the Europeans.

|

As more and more Europeans arrived, violent and legal clashes over land and space began to increase.

|

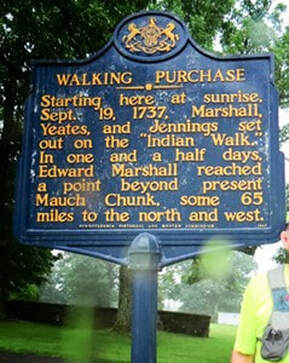

A famous example of an unscrupulous tricky European land acquisition was the Walking Purchase of 1737. The sons of William Penn and a man named James Logan convinced several Lenape chiefs into selling all the land that could be walked in a day and a half’s time.

The Europeans carved out a fast route and trained the men who were going to do the walking. Exhausted by the pace, two Lenape men and two Europeans dropped out, leaving the last man to run 55 miles. A total of 1200 square miles were stolen from the native people that day. |

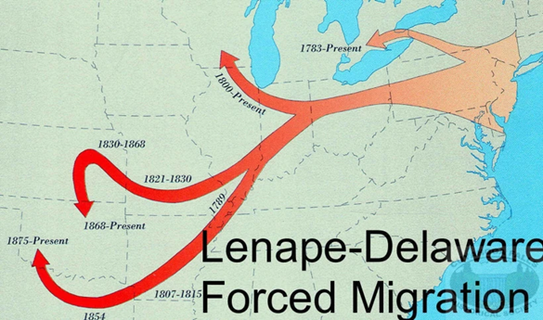

By the early 1700s, some Native Americans were pressured to leave New Jersey to find new homes in the west. Others assimilated into European culture. Some that stayed in New Jersey resented the colonization of their homeland and raided European settlements during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

In 1756, a colonial commission on Indian affairs was created with the goal of resolving conflicts. In 1758, a peace conference was held and some Indians were paid for their land. Even more Lenape groups left their homes to go westward. The colonial New Jersey government also created the first Indian reservation in 1758. Some of the Lenape were relocated to the Brotherton reservation, located in what is now Indian Mills, NJ in Burlington County. The missionary Reverend John Brainerd ran the reservation, but it failed, as the land was not productive, and the Lenape continued to be harassed by colonists.

In 1756, a colonial commission on Indian affairs was created with the goal of resolving conflicts. In 1758, a peace conference was held and some Indians were paid for their land. Even more Lenape groups left their homes to go westward. The colonial New Jersey government also created the first Indian reservation in 1758. Some of the Lenape were relocated to the Brotherton reservation, located in what is now Indian Mills, NJ in Burlington County. The missionary Reverend John Brainerd ran the reservation, but it failed, as the land was not productive, and the Lenape continued to be harassed by colonists.

Few Lenape remain in their ancestral lands today. Those who joined other tribes had to move again as white settlers expanded westward. Regardless of where they ended up, Native Americans across the country continued to be oppressed by colonial expansion and only gained citizenship in 1924.

In 1982, the New Jersey government acknowledged the Powhatan Renape, Ramapough Lenape, and Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribes. Subsequently, state recognition was dropped during the Christie administration. In 2017, the Nanticoke sued the state to regain their recognition. In 2018 and 2019, the NJ state Attorney General officially recognized the existence of the Ramapough Lenape, Powhatan Renape, and Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape nations. This state recognition qualifies the tribes for all state and federal benefits and rights.

These three tribes and other smaller groups of indigenous people in New Jersey still celebrate their culture and history. The remnants of the great expanse of Lenape people can still be found across New Jersey in town names, waterway names, and other features of the landscape.

Click on the images below to visit websites relating to New Jersey's three recognized tribal nations.

In 1982, the New Jersey government acknowledged the Powhatan Renape, Ramapough Lenape, and Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribes. Subsequently, state recognition was dropped during the Christie administration. In 2017, the Nanticoke sued the state to regain their recognition. In 2018 and 2019, the NJ state Attorney General officially recognized the existence of the Ramapough Lenape, Powhatan Renape, and Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape nations. This state recognition qualifies the tribes for all state and federal benefits and rights.

These three tribes and other smaller groups of indigenous people in New Jersey still celebrate their culture and history. The remnants of the great expanse of Lenape people can still be found across New Jersey in town names, waterway names, and other features of the landscape.

Click on the images below to visit websites relating to New Jersey's three recognized tribal nations.

During Trent's Time

The son of William Trent of Inverness, William Trent’s date of birth is uncertain. Some sources indicate that he was born about 1653-1655 in the Scottish Highlands; others attribute the date of his birth to 1666 when he was baptized at South Leith in southeast Scotland. Exactly when he emigrated to the American colonies is also unknown. Based on Philadelphia tax rolls in 1693, we know that he had followed his brother James to that city.

Trent as a Man of Business

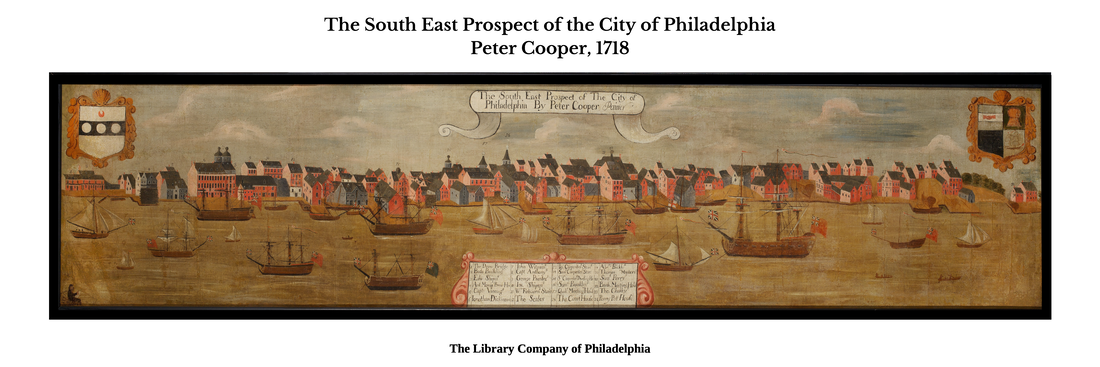

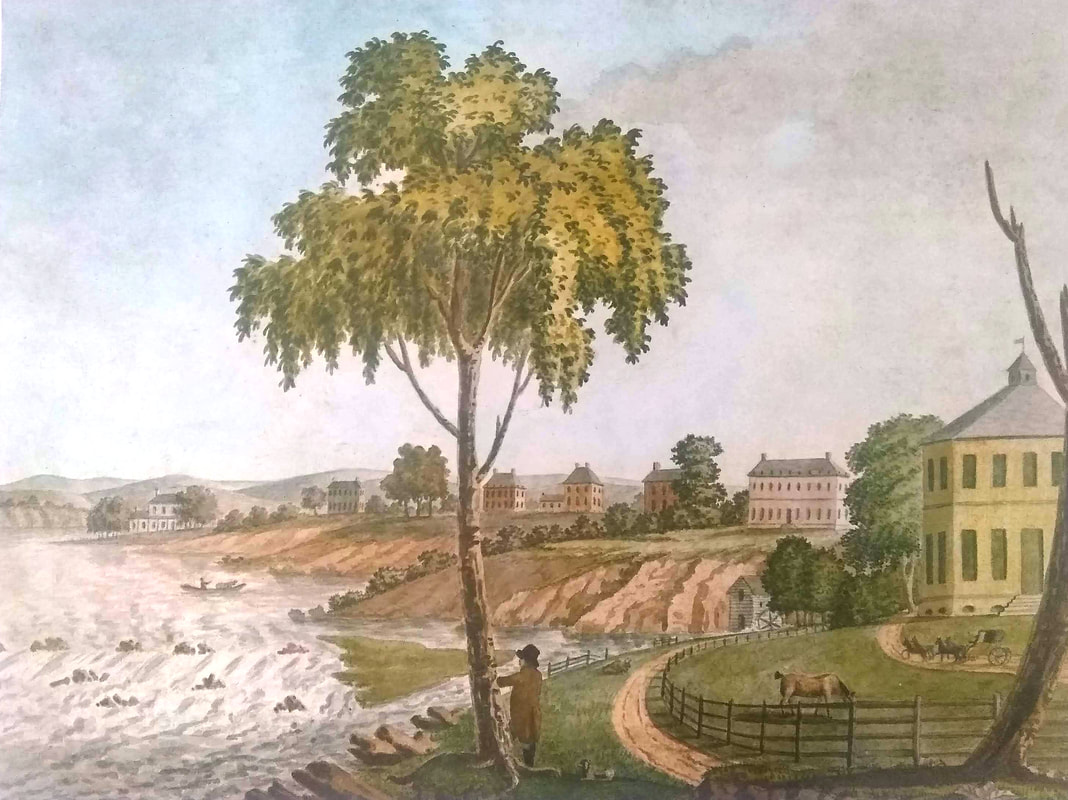

William Trent became a very successful and wealthy merchant in Philadelphia, trading with Great Britain and the English colonies on the mainland and in the West Indies. At one time he owned an interest in over forty ships, exporting such products as tobacco, flour, and furs, while importing wine, rum, molasses, and dry goods. The image below depicts the busy harbor of Philadelphia during Trent's time.

|

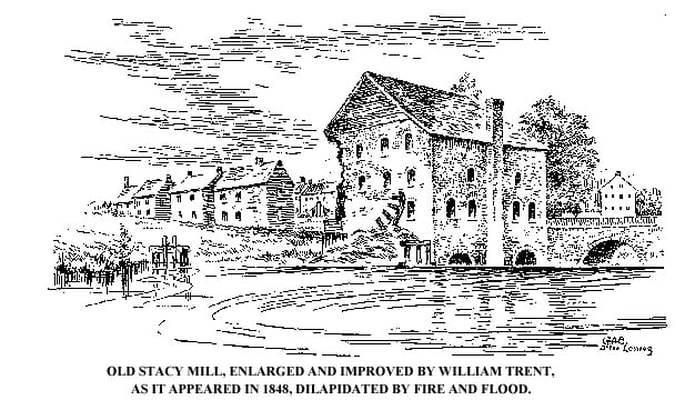

After purchasing the large tract of land in New Jersey from Mahlon Stacy's son in 1714 Trent had established several mills on his plantation along the Assunpink Creek, producing flour, lumber, and cloth, increasing his wealth. By the time Trent died in 1724, his enterprises in Trent’s Town had continued to expand and diversify. In Mary Coddington Trent’s suit against James Trent, her oldest stepson from Trent’s first marriage, she claimed her share in three grist mills, one saw mill, one fulling mill, one bake house, one dye house, one ferry house, and half an ironwork. |

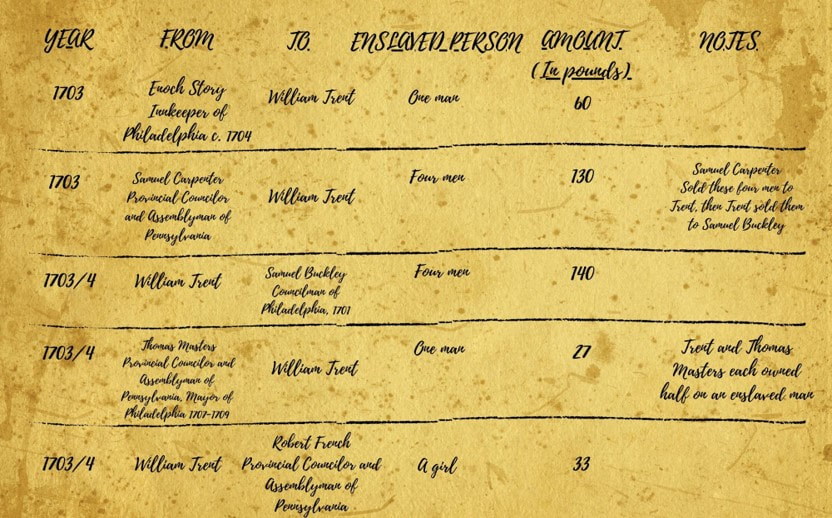

Wealth Created from Slavery

Slavery was central to Trent's wealth. Trent was active in the slave trade, buying and selling enslaved people of African descent. We know of thirteen such transactions with other prominent Philadelphia men in just the few years (1703-1708) covered by trade ledgers in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Several of these transactions are illustrated below and a complete listing can be seen here.

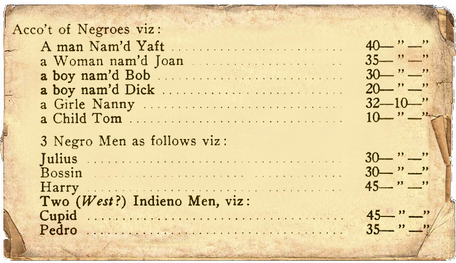

Listed on the probate inventory conducted after Trent's death and completed in mid-1726 are eleven enslaved people – six men (Yaff, Julius, Bossin, Harry, Cupid, and Pedro), one woman (Joan), two boys (Bob and Dick), one girl (Nanny), and one male child (Tom). These people not only comprised about one-third of the value of Trent's belongings at the time of his death, but also made his life at the Falls of the Delaware comfortable and of elite status and continued building his wealth through their work on Trent's farms and mills.

For example, in a letter written on May 17, 1721, from Philadelphia to his eldest son James, Trent mentions Harry, one of the men enslaved on his plantation at the Falls of the Delaware,. On the probate inventory compiled after Trent’s death in 1724, Harry is assessed at 45 pounds, which is the highest monetary value given to any of the eleven enslaved people. The letter gives us some clues about why: "I hope all the Wheat is Ground & Bolted. You must gett Harry to help them in the Bake house till the Stuff [is] bak’t up. Ile be up as soon as I cane dispatch the Shalop down wth the Flower & Bread." (A shalop or shallop is a light river boat with both sails and oars.) Trent’s reliance on Harry to assist in bread production suggests that he was both a skilled and a productive baker.

For example, in a letter written on May 17, 1721, from Philadelphia to his eldest son James, Trent mentions Harry, one of the men enslaved on his plantation at the Falls of the Delaware,. On the probate inventory compiled after Trent’s death in 1724, Harry is assessed at 45 pounds, which is the highest monetary value given to any of the eleven enslaved people. The letter gives us some clues about why: "I hope all the Wheat is Ground & Bolted. You must gett Harry to help them in the Bake house till the Stuff [is] bak’t up. Ile be up as soon as I cane dispatch the Shalop down wth the Flower & Bread." (A shalop or shallop is a light river boat with both sails and oars.) Trent’s reliance on Harry to assist in bread production suggests that he was both a skilled and a productive baker.

Family Life

|

In the 1690s he married his first wife, Mary Burge, with whom he had three children, James, John, and Maurice. Apparently it was through her family connections that William Trent eventually acquired the land at the Falls of the Delaware River where he would build his country seat. She died, perhaps in childbirth, in 1708, and a contemporary noted in a letter to William Penn that Trent was greatly affected by her death. To the right is an image of the Slate Roof House, which was the Trents' residence in Philadelphia. |

|

In 1710 Trent married his second wife, Mary Coddington, who was in her late teens at the time of her marriage. Born into a wealthy family, she was the stepdaughter of Anthony Morris, a prosperous Philadelphia brewer and merchant who was a business associate and contemporary of her new husband. In 1711, Mary Coddington Trent gave birth to a son, Thomas, who died that same year. Another son, William, was born in 1715 and survived. The couple and Trent’s children from his previous marriage continued to live in Philadelphia as their primary residence until 1721, when Trent made his plantation on the Falls of the Delaware his permanent home for himself, his second wife, and his youngest son. |

While a resident of the New Jersey colony, Trent was elected to the Assembly, commissioned a colonel in one of the militia regiments, and in 1723 became New Jersey’s first resident Chief Justice.

On Christmas Day 1724 William Trent died suddenly from a “fit of apoplexy,” or what we might call today a stroke. At the time of his death, Trent was between the ages of 58 and 69. His widow was in her early 30s, and her son, William, was 9.

On Christmas Day 1724 William Trent died suddenly from a “fit of apoplexy,” or what we might call today a stroke. At the time of his death, Trent was between the ages of 58 and 69. His widow was in her early 30s, and her son, William, was 9.

After Trent's Death

Trent’s oldest son, James, inherited his father’s entire estate when Trent died without a will. Mary Coddington Trent renunciated her role as executor in March of 1725 so she could obtain her dower rights by suing her stepson James. She hired well known Philadelphia attorney John Kinsey to sue for one-third part of the income from four messuages (dwelling houses with considerable land), three grist mills, one saw mill, one fulling mill, one bake house, one dye house, one ferry house, half an ironwork, one barn, three gardens, two orchards, thirty acres of meadowland, three hundred acres of pastureland, and two hundred acres of woodland.

Mary won her court case in 1728. Her stepson James and subsequently William Morris, her half-brother, had to pay the mortgage on the estate to her from 1729-1735. This included profits and ownership of the mills and other industries on the property. She sold all rights to most of these properties to George Thomas in 1735. However, Joseph Peace, head miller of the mills on the Assunpink, made payments to her until 1750 when he sold the mills to Robert Hooper. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mary Coddington Trent never remarried, thus retaining control over her property until she died on December 15, 1772, in her 80s. Her death is recorded in the register of Saint Michael’s Church and she is most likely buried in the Hopewell Church Burying Ground on the site of the modern day Trenton Psychiatric Hospital.

Mary won her court case in 1728. Her stepson James and subsequently William Morris, her half-brother, had to pay the mortgage on the estate to her from 1729-1735. This included profits and ownership of the mills and other industries on the property. She sold all rights to most of these properties to George Thomas in 1735. However, Joseph Peace, head miller of the mills on the Assunpink, made payments to her until 1750 when he sold the mills to Robert Hooper. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mary Coddington Trent never remarried, thus retaining control over her property until she died on December 15, 1772, in her 80s. Her death is recorded in the register of Saint Michael’s Church and she is most likely buried in the Hopewell Church Burying Ground on the site of the modern day Trenton Psychiatric Hospital.

Click Image to Enlarge

Click Image to Enlarge

A probate inventory of Trent's estate, completed in 1726, listed the furnishings of the House as well as other items on the plantation. Included on the inventory was an “Account of Negroes” that included eleven enslaved people – six men (Yaff, Julius, Bossin, Harry, Cupid, and Pedro), one woman (Joan), two boys (Bob and Dick), one girl (Nanny), and one male child (Tom). For more information see our work on slavery interpretation.

The inventory gives the values of each of these people, as was the case for all other entries, in English currency of the time and groups the eleven into three groups. The first group included Yaff, Joan, the two boys (probably between 10 and 15 years of age) Bob and Dick, the girl Nanny, and the child Tom. We currently interpret these people as working and living in the house. The other two groups are adult men - Julius, Bossin, Harry, Cupid, and Pedro - who probably worked on the plantation and mills in various capacities. For example, we know from a letter written by Trent to his eldest son James that Harry worked in the bakery producing bread for sale in Philadelphia.

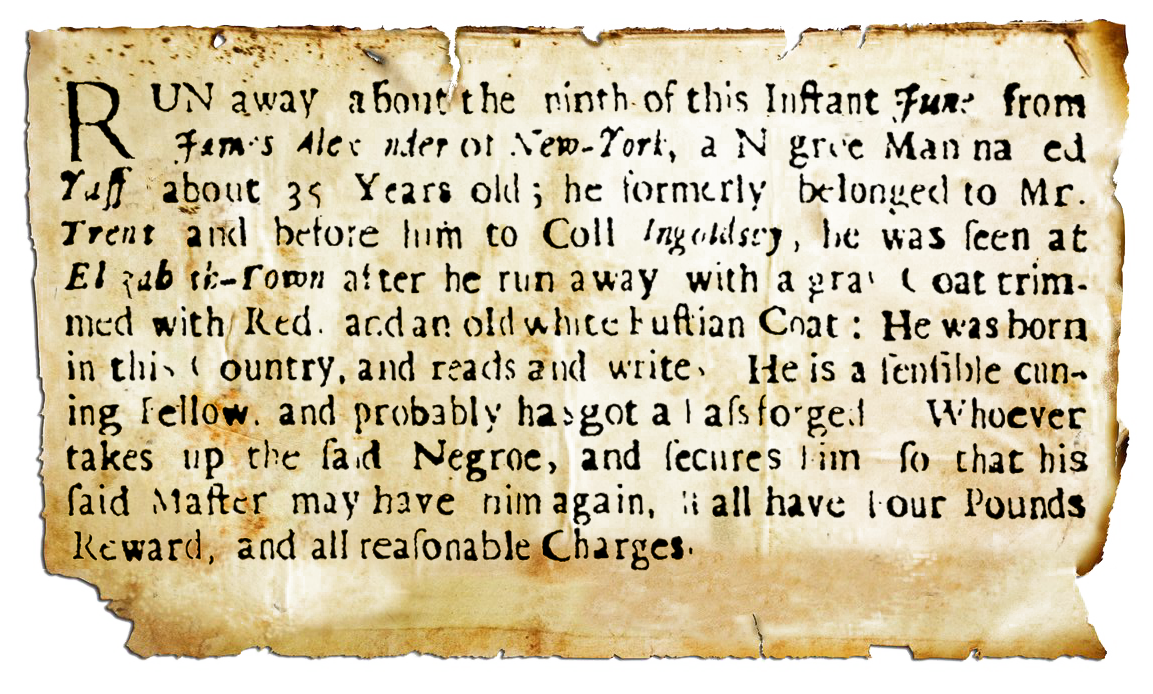

Yaff, who we believe was Trent’s butler and valet, was sold to James Alexander of New York, one of the executors of Trent’s estate. In June 1729 he sought his freedom by escaping. Alexander took an advertisement in the New York Gazette, offering a reward of 4 pounds for his return. The advertisement, shown below with a transcription, provides us with some details of Yaff’s age, personal history, skills, and personality. Unfortunately, we do not know if he was captured or remained free.

The inventory gives the values of each of these people, as was the case for all other entries, in English currency of the time and groups the eleven into three groups. The first group included Yaff, Joan, the two boys (probably between 10 and 15 years of age) Bob and Dick, the girl Nanny, and the child Tom. We currently interpret these people as working and living in the house. The other two groups are adult men - Julius, Bossin, Harry, Cupid, and Pedro - who probably worked on the plantation and mills in various capacities. For example, we know from a letter written by Trent to his eldest son James that Harry worked in the bakery producing bread for sale in Philadelphia.

Yaff, who we believe was Trent’s butler and valet, was sold to James Alexander of New York, one of the executors of Trent’s estate. In June 1729 he sought his freedom by escaping. Alexander took an advertisement in the New York Gazette, offering a reward of 4 pounds for his return. The advertisement, shown below with a transcription, provides us with some details of Yaff’s age, personal history, skills, and personality. Unfortunately, we do not know if he was captured or remained free.

|

"Run away about the ninth of this instant June from James Alexander of New York, a Negroe man named Yaff about 35 years old; he formerly belonged to Mr. Trent and before him to Coll Ingoldsey, he was seen at Elizabeth-Town after he run away with a gray coat trimmed with red and an old white fustian coat: He was born in this country and reads and writes. He is a sensible, cunning fellow and probably has got a pass forged. Whoever takes up the said Negroe, and secures him so that his said master may have him again, shall have four pounds reward and all reasonable charges." June 1729 - New York Gazette |

In March of 1737, two enslaved African men were arrested in Trenton for "practising poison," citing among their victims William Trent. They were found guilty and hanged. It is not known if Trent was actually murdered, or if his sudden death was later used by these men as “proof” of the efficacy of their poison. For more information on this case, the question of whether Trent was poisoned, and the laws under which the men were charged and executed,

see here.

Major William Trent, Trent’s youngest son by his marriage to Mary Coddington, led a fascinating life. He was a fur trader, military leader, and land speculator on the colonial frontier. He, along with young Colonel George Washington, was sent by the Royal Governor of Virginia to establish a fort at the Forks of the Ohio River near what is now Pittsburgh to defend English control of the frontier from the French.

The Trent House is honored to own his silk waistcoat, worn at the Court of St. James in 1769, as he sought repayment for losses he and other traders experienced during the French and Indian War. While the waistcoat itself is in storage, visitors to the Museum can see close-up photographs of it on display.

To learn more about Major Trent and the Trent family history, contact Jason Cherry, Trent House consultant researcher, at [email protected].

During the American Revolution, the Trent House grounds were occupied by Hessian forces and played a role in several battles fought at Trenton during December of 1776. Dr. William Bryant, the owner of the property at that time, was later expelled for his Tory sympathies. Colonel John Cox, a wealthy Philadelphia patriot and Deputy Quartermaster General of the Continental Army, acquired the house and turned the grounds into a supply depot for Washington’s army.

The house returned to prominence in 1835 when Philemon Dickerson, a well-known Jacksonian Democrat, purchased it. The following year he was elected Governor and used the Trent House as his Official Residence.

Again in 1854 it served as the Official Residence of the Governor when the property was purchased by Governor Rodman McCamley Price. Price, a Democrat, made his fortune in the San Francisco Gold Rush of 1849, returning to New Jersey to enter politics.

In 1929 the last private owner of the Trent House, Edward A. Stokes, donated the building to the City of Trenton in 1929 with the condition that it be returned to its appearance during the William Trent era and be used as a library, art gallery or museum. The House opened as a museum in 1936 after extensive restoration as a Works Progress Administration project.