Inventory

|

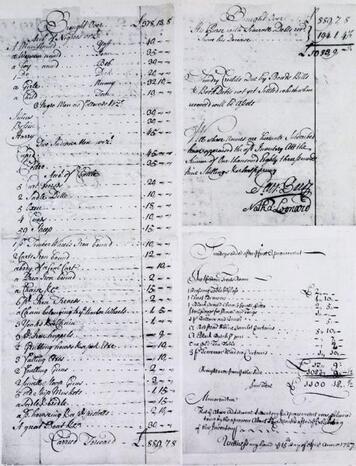

An inventory of a decedent’s property was typically taken within thirty days of a death in order to determine the estate. Trent's probate inventory was conducted in April 1726, more than a year after his death, with an addendum one year later. Click here to download a complete printer-friendly transcription of the inventory.

When a greater period of time has elapsed between an individual’s death and the inventory (16 months, in Trent’s case), it suggests that the estate was contested – which was certainly the case of William Trent. Since William Trent died without a will, his estate was contested between his eldest son, James, and his widow, Mary Coddington Trent. Mary Trent’s possessions were inventoried separately by others and are listed at the end of the inventory. Mary’s suit was successful and she received income in rents and mortgage payments from Trent’s mills and other property. Click here to read more under "After Trent's Death". Eighteenth century inventories included household goods and personal possessions such as clothing and jewelry, real estate, cash, or bonds, tools of trade, shop inventories in the case of a merchant, livestock, outbuildings, farm implements, as well as people who were enslaved by or indentured to the decedent. Trent’s probate inventory included information on eleven enslaved people of African descent - six adult men (Yaff, Julius, Bossin, Harry, Cupid, and Pedro), one adult woman Joan, two boys Bob and Dick, a girl Nanny, and a child Tom. For more information see our work on slavery interpretation. |

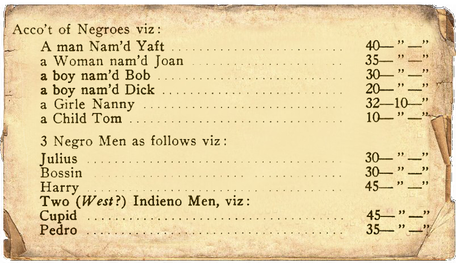

Enslaved People on Trent's Probate Inventory

|

Like all other items on the inventory, the assessed value of each enslaved individual is given in pounds, shillings, and pence, with some of the men more highly valued than the one adult woman, the boys and girl, and the child. The high value of Yaff, Harry, and Cupid likely reflected their skills as well as their position in Trent’s household. We interpret Yaff as the butler and personal servant to Mr. Trent and the other individuals listed with him (Joan, Bob, Dick, Nanny, and Tom) as household servants living in the house with Trent's family. The other five adult men are assumed to have worked on Trent's farms and orchards or in his mills on Assunpink Creek. |

A runaway slave advertisement from 1729 for Yaff, identifying him as formerly owned by Mr. Trent, reports that he escaped from his current owner in livery, suggesting that he continued to serve in that role after being sold after Trent’s death. Click here to read more under "After Trent's Death." In addition, the advertisement indicates that Yaff could read and write, a skill denied many enslaved people. From a letter written by William Trent to his eldest son James we know that Harry was important in managing the bake house producing bread for shipping to Philadelphia.

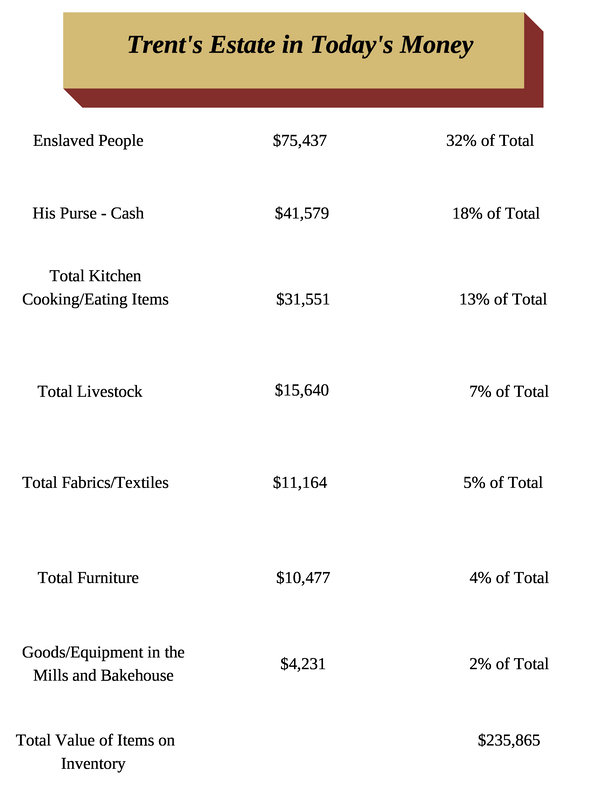

All together the assessed value of the eleven enslaved people totaled about one-third of Trent’s property apart from the land, buildings, and mills. This is illustrated here, in which assessed values from the inventory are shown in U.S. dollars and cents.

Slavery was central to Trent's wealth. Trent was active in the slave trade, buying and selling enslaved people of African descent. We know of thirteen such transactions with other prominent Philadelphia men in just the few years (1703-1708) covered by trade ledgers in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The eleven people listed on the probate inventory conducted after Trent's death not only comprised about one-third of the value of Trent's belongings at the time of his death, but also contributed to building his wealth by working in his mills and other business enterprises. For example, we know that Trent relied on Harry to manage production in the bake house, where bread was baked for sale in Philadelphia.

The Trent House acknowledges that enslaved African people contributed to much of William Trent's wealth through slavery and shares what we know through exhibits, programs, tours, and digital communication.

Other Entries on the Inventory

The specificity of information recorded on the inventory varied a great deal. Some items are described in detail: 2 Large peer Glasses with Sollpopt Shells gilt with gold, which tells us the type of looking glass (peer glass), its size (large), finish (gilt with gold), and decoration (scalloped shells). Other entries, such as 12 Small Chears, tells us little about the group of chairs from the lower front hall, except their size and number.

Although the inventory does not provide exact information about how the Trent home was furnished, much can be learned about the household and their way of life by closely studying this document. The large number of kitchen implements indicates frequent meals and generous entertaining, for which considerable cost and enslaved labor must have been expended. Similarly there are numerous brooms and brushes, required for frequent cleaning of the wood floors and nine fireplaces.

Although the inventory does not provide exact information about how the Trent home was furnished, much can be learned about the household and their way of life by closely studying this document. The large number of kitchen implements indicates frequent meals and generous entertaining, for which considerable cost and enslaved labor must have been expended. Similarly there are numerous brooms and brushes, required for frequent cleaning of the wood floors and nine fireplaces.

|

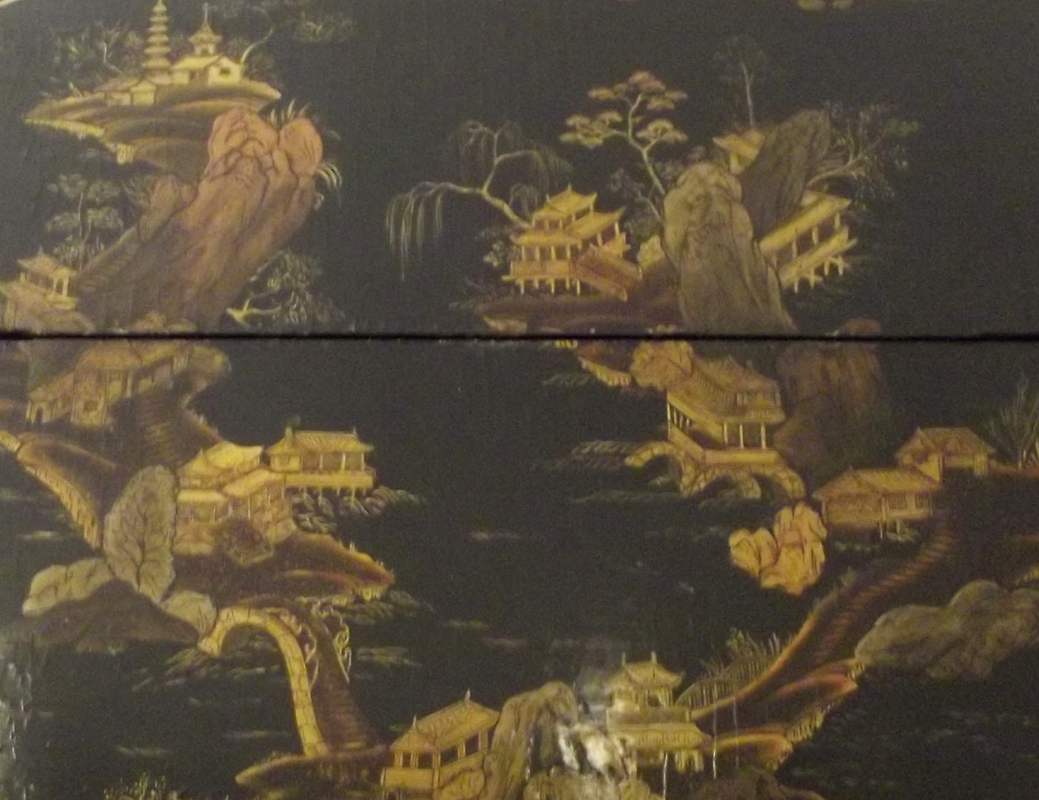

Several pieces of furniture japanned in gold confirms that Trent has access to the high-style imported furniture popular at the time in large colonial cities like Philadelphia and New York.

In the 18th century, the Japanese method of painting elaborate scenes in gold on a black lacquered background being copied in China was called Japanning. |

Japanned furniture imported from China was very popular among the wealthy both in Europe and the American colonies. Trent's probate inventory lists several pieces of Japanned furniture and given their cost was a symbol of his wealth and status.

The large supply of table silver (referred to as “New” and “old” Plate) demonstrates that Trent was quite wealthy by any standard. His wealth is also indicated by the number and value of his enslaved workers, which equals about one-third of the inventory assessment.

The inclusion of sundries from the Grist, Saw, and “foulling” (fulling) Mills and the bake-house shows the diversification of Trent’s business interests in the town. The “great Boat” confirms travel to and from his estate by ship via the Delaware River. “Sloop Guns” and “Ship Muskets” indicate that river travel could be dangerous in this very early period of colonial history.

Interestingly, Trent’s inventory lists no portraits or paintings. The only mention of pictures is the notation of “Eight Indian Pictures Without Frames.” It is possible that some family treasures could have been distributed among the three adult sons from Trent’s first marriage, prior to the making of this inventory, since more than a year elapsed between his death in December 1724 and the estate appraisal in April 1726.

The inventory itself is on file in the office of the Superior Court of New Jersey, State House Annex, contained in a bound volume filed as 1211-1216C, 1433-1448C.

The large supply of table silver (referred to as “New” and “old” Plate) demonstrates that Trent was quite wealthy by any standard. His wealth is also indicated by the number and value of his enslaved workers, which equals about one-third of the inventory assessment.

The inclusion of sundries from the Grist, Saw, and “foulling” (fulling) Mills and the bake-house shows the diversification of Trent’s business interests in the town. The “great Boat” confirms travel to and from his estate by ship via the Delaware River. “Sloop Guns” and “Ship Muskets” indicate that river travel could be dangerous in this very early period of colonial history.

Interestingly, Trent’s inventory lists no portraits or paintings. The only mention of pictures is the notation of “Eight Indian Pictures Without Frames.” It is possible that some family treasures could have been distributed among the three adult sons from Trent’s first marriage, prior to the making of this inventory, since more than a year elapsed between his death in December 1724 and the estate appraisal in April 1726.

The inventory itself is on file in the office of the Superior Court of New Jersey, State House Annex, contained in a bound volume filed as 1211-1216C, 1433-1448C.