Archaeological Investigations

A dig open to the public on Trent House grounds

A dig open to the public on Trent House grounds

Archaeology as History

The Trent House site encompasses thousands of years of history, both recorded and not. In researching a place like the Trent House, the fields of archaeology and history often overlap; this is the field of Historical Archaeology.

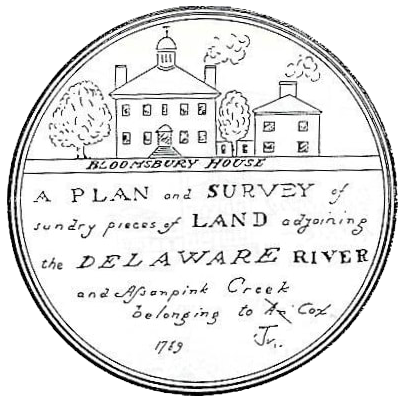

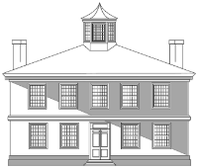

When excavating, archaeologists can use historical records and documents to guide their research. For instance, the 2015 excavations done by Hunter Research unearthed the remains of the 18th century kitchen wing, and they knew it was there based on a historical drawing of the house.

Excavations with the goal of unearthing Colonial or later era items are a little easier to plan, since historical data can be used in conjunction with technology like ground penetrating radar. Prehistoric excavations are harder to plan for.

Evidence for Native American occupation at the site has been found while archaeologists were searching for colonial artifacts. While there are no official records of where ancient people lived, archaeologists can use clues from the landscape to infer where people might have lived.

We can fill in the gaps of our knowledge of the people called Lenape through European written sources. The Europeans learned that the Native Americans they encountered called themselves Lenape. The groups that lived before that are only known to us through archaeological evidence or oral traditions passed down through generations of Native American people.

The Trent House site encompasses thousands of years of history, both recorded and not. In researching a place like the Trent House, the fields of archaeology and history often overlap; this is the field of Historical Archaeology.

When excavating, archaeologists can use historical records and documents to guide their research. For instance, the 2015 excavations done by Hunter Research unearthed the remains of the 18th century kitchen wing, and they knew it was there based on a historical drawing of the house.

Excavations with the goal of unearthing Colonial or later era items are a little easier to plan, since historical data can be used in conjunction with technology like ground penetrating radar. Prehistoric excavations are harder to plan for.

Evidence for Native American occupation at the site has been found while archaeologists were searching for colonial artifacts. While there are no official records of where ancient people lived, archaeologists can use clues from the landscape to infer where people might have lived.

We can fill in the gaps of our knowledge of the people called Lenape through European written sources. The Europeans learned that the Native Americans they encountered called themselves Lenape. The groups that lived before that are only known to us through archaeological evidence or oral traditions passed down through generations of Native American people.

Archaeology in Practice

Archaeology is a slow paced-profession. Extensive planning and research (when applicable) is required before any digging starts. Excavations are done in careful layers, with every step of the process documented. After excavations are over, archaeologists analyze all of their findings and write a site report. The findings on this page are written through an archaeological view of the past.

In 1995, the cultural resource management firm Hunter Research performed archaeological investigations and historical research in connection with repairs to the Trent House tunnel. Two trenches were excavated across the line of the tunnel. Native American artifacts were found including a projectile point dating to between 3000 and 1700 B.C. From 2000-2003, a public archaeology program was implemented with students and volunteers excavating 235 shovel tests on the property. Additionally, an excavation unit was dug which produced prehistoric and historic artifacts, pre-20th century soils and historic features. Historic artifacts included Dutch bricks and sugar molds from the nearby William Richards pottery of the 1770s and 1780s.

Archaeology is a slow paced-profession. Extensive planning and research (when applicable) is required before any digging starts. Excavations are done in careful layers, with every step of the process documented. After excavations are over, archaeologists analyze all of their findings and write a site report. The findings on this page are written through an archaeological view of the past.

In 1995, the cultural resource management firm Hunter Research performed archaeological investigations and historical research in connection with repairs to the Trent House tunnel. Two trenches were excavated across the line of the tunnel. Native American artifacts were found including a projectile point dating to between 3000 and 1700 B.C. From 2000-2003, a public archaeology program was implemented with students and volunteers excavating 235 shovel tests on the property. Additionally, an excavation unit was dug which produced prehistoric and historic artifacts, pre-20th century soils and historic features. Historic artifacts included Dutch bricks and sugar molds from the nearby William Richards pottery of the 1770s and 1780s.

|

Historic features include an 18th century mica schist footing thought to be the southern wall of the covered walkway leading to the 18th century kitchen. A part of a 19th century foundation was also found, believed to be part of the 19th century eastern wing. In 2002, archaeologists investigated the sides of construction trenches in which 17th, 18th 19th and 20th century features were found.

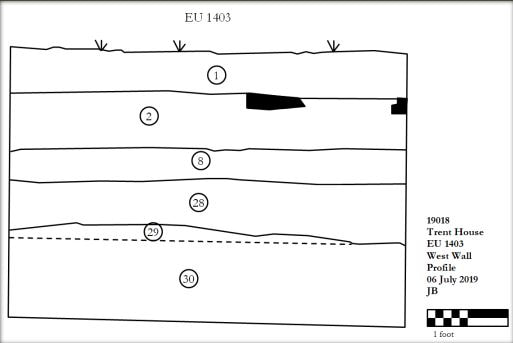

In 2015, Hunter Research performed archaeological excavations on the east side of the house. This investigation exposed the foundations of the prominent mid-18th century kitchen wing, a free-standing, two-story structure connected to the house by a gangway. A total of 2539 historic and prehistoric artifacts were recovered as well as several historic features including one interpreted to be the south wall of the 1742 Lewis Morris kitchen wing and remnants of the attached gangway. The former kitchen wing, shown here in a drawing from 1789, is no longer visible on the property, but these excavations hinted that more information about the use and occupation of this wing are waiting to be discovered beneath the ground surface. |

|

During the summer of 2019, with funding from NJM Insurance Group and the Trent House Association, a team of professional archaeologists from Hunter Research and Monmouth University undertook new investigations. Expanded exploration of and near the 1742 kitchen site revealed additional evidence of its foundation and structure. Richard Hunter, James Lee, and Richard Veit summarized findings from that excavation in a talk at the Trent House on July 24, 2022. A recording of their talk, "Governor Morris' Kitchen and Other Findings from Archaeology at the Trent House," can be viewed from the Videos & Recordings page.

The work also investigated a new area to the south of the House; this site produced extensive artifacts from Native American settlement on the site as well as from European occupation in the 1600s and 1700s, examples of which are shown below. For a recent analysis of Native American archaeological artifacts found on the Trent House property, see here. Additional investigations have included a ground penetrating radar study in 2016 and deep soil sampling using augering in 2020. For an overview of archaeology at the Trent House see here. Students and adults can learn about the basics of archaeology and how archaeological research on the Trent House site has informed our understanding of Native American life and take a quiz to see how much they now know by clicking here. |

Pictured at left is a Bellarmine jug shard. It was made in Western Germany and found on site. AKA Bartmann jugs (16th thru 17th century). |

Native American Occupation

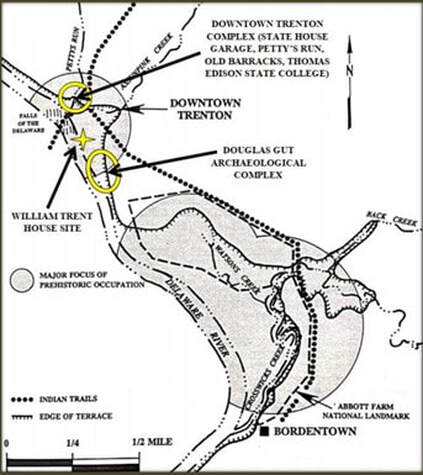

Map of central NJ archaeological complexes

Map of central NJ archaeological complexes

Using Archaeology to Discover Ancient Lives

Where the Trent House stands today used to be an intersection of Native American trails. This site is also very close to the falls of the Delaware River, which makes it a good place for fishing. The House stands on a small knoll that overlooks the surrounding area, which would have been very useful in prehistoric times. While there were no villages on the Trent House site, seasonal occupation and mobile groups left traces of their lives here.

Many archaeological excavations have been completed in Trenton, as well as some in the surrounding towns. These projects have found thousands of Native American artifacts from many different prehistoric time periods. Some excavations occur by law when a location is undergoing construction, and others are done for educational purposes, like those done at the Trent House by Hunter Research. More than 5,000 artifacts have been found on site at the Trent House, many of them Native American.

Ancient Native American occupation is broken down into different eras. In New Jersey history, there are three: the Paleoindian, the Archaic, and the Woodland. The distinctions between the periods are based on technology, tools, types of common activities and occasionally climate patterns. To learn more about each period in detail, click here.

Where the Trent House stands today used to be an intersection of Native American trails. This site is also very close to the falls of the Delaware River, which makes it a good place for fishing. The House stands on a small knoll that overlooks the surrounding area, which would have been very useful in prehistoric times. While there were no villages on the Trent House site, seasonal occupation and mobile groups left traces of their lives here.

Many archaeological excavations have been completed in Trenton, as well as some in the surrounding towns. These projects have found thousands of Native American artifacts from many different prehistoric time periods. Some excavations occur by law when a location is undergoing construction, and others are done for educational purposes, like those done at the Trent House by Hunter Research. More than 5,000 artifacts have been found on site at the Trent House, many of them Native American.

Ancient Native American occupation is broken down into different eras. In New Jersey history, there are three: the Paleoindian, the Archaic, and the Woodland. The distinctions between the periods are based on technology, tools, types of common activities and occasionally climate patterns. To learn more about each period in detail, click here.

Artifacts are sorted into periods by archaeologists based on their identifying factors. For instance, the projectile point on the left is from the Archaic Period. Archaeologists know this based on comparison to other existing artifacts. Sometimes, artifacts can be dated by the soil layer they were excavated in, if there was no disturbance.

The identifying factors of this point are its material (argillite), its size, its shape, and where the notches in the point are. Click on the image to go to a website with New Jersey projectile point typologies.

Argillite Projectile Point, Late Archaic Period (4,000 to 2,000 BCE).

The identifying factors of this point are its material (argillite), its size, its shape, and where the notches in the point are. Click on the image to go to a website with New Jersey projectile point typologies.

Argillite Projectile Point, Late Archaic Period (4,000 to 2,000 BCE).

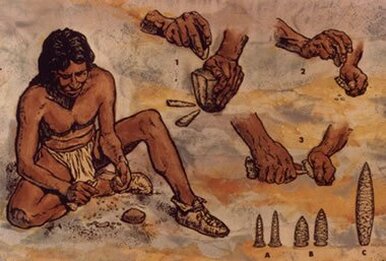

Illustration of a Native American creating a stone tool

Illustration of a Native American creating a stone tool

Toolmaking

Tool making, or flintknappping, usually begins with a large chunk of rock. In New Jersey, common stone types are jasper, chert, argillite and quartz. The flintknapper hits off pieces

of the rock using a hammerstone or antler. This is called chipping and flaking. Flakes were likely turned into tools themselves.

For finer details like notches and edges, pressure flaking is used. A small tool, usually the end of an antler, is pressed onto the rock to make the desired shape. Projectile points are made this way.

Another method of rough shaping is pecking and grinding. A hammerstone is hit against a rock to shape it, and the edges are rubbed on another surface to smooth them. Axes and other tools are commonly made this way.

Tool making, or flintknappping, usually begins with a large chunk of rock. In New Jersey, common stone types are jasper, chert, argillite and quartz. The flintknapper hits off pieces

of the rock using a hammerstone or antler. This is called chipping and flaking. Flakes were likely turned into tools themselves.

For finer details like notches and edges, pressure flaking is used. A small tool, usually the end of an antler, is pressed onto the rock to make the desired shape. Projectile points are made this way.

Another method of rough shaping is pecking and grinding. A hammerstone is hit against a rock to shape it, and the edges are rubbed on another surface to smooth them. Axes and other tools are commonly made this way.

Toolmaking is also a way to study trade between pre-contact Native Americans. Stones that are sourced from Maryland found in New Jersey sites, for instance, show that groups of people from each region traded with each other.

Some people still practice the art of flintknapping today, and many videos can be found all over the internet. Flintknapping was, and still is, dangerous. Modern flintknappers report injuries to their fingers, hands and legs. Ancient people had to be careful and skilled to avoid major injuries.

Some people still practice the art of flintknapping today, and many videos can be found all over the internet. Flintknapping was, and still is, dangerous. Modern flintknappers report injuries to their fingers, hands and legs. Ancient people had to be careful and skilled to avoid major injuries.

|

On Display at the Trent House Visitor Center

There are two displays dedicated to archaeology at the Trent House. One is for Native American artifacts, and other contains colonial era artifacts. In the Native American case, there is a variety of projectile points, stone tools, and some pottery. Click the image to see a digital copy of our flintknapping booklet that accompanies our Native American artifacts in the museum. The display also has a timeline of Native American history in New Jersey on top of the case. The colonial case contains ceramic sherds, pieces of bottles, pipe fragments, bones and shells from the kitchen excavation. The New Jersey State Museum loaned the Trent House a large piece of pottery to improve the display. Please consider visiting their new exhibit, "History Beneath Our Feet: Archaeology of a Capital City" at 205 West State Street, Trenton, NJ. |